APIs: A starter guide for Librarians

A LIBER Digital Scholarship & Data Science Topic Guide for Library Professionals

Introduction

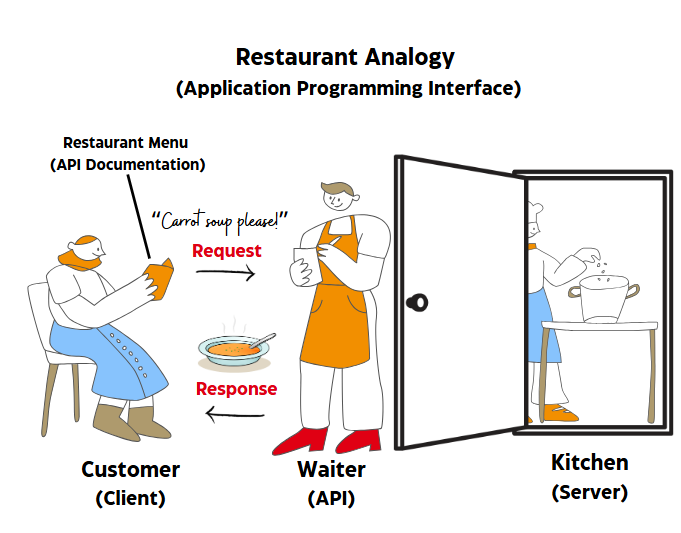

APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) can sound intimidating, but the ideas behind them are not unfamiliar. An application programming interface (API) allows a connection between computers or between computer programs; it is a type of software interface offering a service to other pieces of software. A common analogy that can be helpful in understanding the process of how APIs work is the restaurant analogy.

Imagine going to a restaurant (server). You first consult the menu provided (API documentation) to understand what is available for you to order (request). After consulting the menu (documentation) you have a good idea of what is likely to result in a successful order from the kitchen. The waiter is a bit like the restaurant’s API. Behind the waiter is a whole world of kitchen staff, bar staff, wholesalers, suppliers, shareholders and so on. You don’t need to worry about any of them, you probably won’t even ever speak to them. All your food orders (requests) and any extra instructions such as “chips or mash?” (parameters) will be passed to the kitchen (server) by the waiter (API). The kitchen (server) prepares your order (request) and passes it to the waiter (API) to deliver to your meal (response).

Just as in our analogy above, sites will offer an API, and anyone can use it without having to know anything about the internal workings of that system. You don’t need to see the source code, the technologies they used to build it, or know the name of the person who keeps it running at weekends. All you need to know is how to make a request to the API, and for this, APIs will normally have a site that will document what you can request and how. A good example is OpenLibrary’s API pages. The API documentation will list what requests you can make. It will also describe what additional information you need to provide when making a request, for example the name of a dish in the restaurant example; the additional pieces of information are referred to as parameters. The documentation may also state any security considerations, such as needing authentication (an API Key) or a log in before using the method. See Lists API | Open Library for examples.

This Topic Guide will focus on REST-based APIs as an example as it’s the most likely you’ll encounter in your day to day library work. Just be aware that other API types exist, such as:

You can find some information on those here: https://www.postman.com/what-is-an-api/#api-architectural-styles

The main thing to keep in mind is the idea that an API enables the exchange of data and information between two systems and provides a protocol between both sides on how to do this. The user gets a documented way to find out how to interact with a system and understand everything that comes back from it. The provider of the service also knows exactly how their system is being interacted with. Again, thinking about this idea in the context of a restaurant, a restaurant might find itself being hugely successful, so makes the decision to move to larger or multiple premises and upgrade its kitchen. If they keep the same menu, then the effect of this on you is minimal – you can still order your favourite dish, despite all the changes!

Making an API request

Types of Requests

Different types of requests are made to an API depending on what you want to do and whether you want to read from the API or send some information back. In a REST API we call these different types of requests “HTTP request methods”, and they are designed as a simple way to describe what you are trying to do. Have a look at Mozilla’s pages on methods for more in-depth details.

The main HTTP request methods are described in the table below:

| HTTP Request Method | Description |

|---|---|

| GET | Reads information from the server, but does not change what is on the server. Example: requesting a list of available images or an individual image. |

| POST | Send information to be handled by the server, possibly adding or changing what is stored on the server. Example: posting a comment on social media. |

| PUT | Upload a new resource or replace an entire existing resource, to a specific location on the server. Example: adding a new item to a database. |

| PATCH | Like PUT, but modifies just part of the existing resource rather than the entire thing. |

| DELETE | Removes a specific resource from the server. Example: delete an item from a database. |

To make these more understandable, let’s substitute in an editor of books in place of all this technology. Our editor character is equivalent to the user of our API, and the author they are working with is equivalent to the API itself. The mail is the equivalent of the Internet and the draft pages of the book are the resources handled by the API.

Our editor starts the day by GETting a draft version of a book from the author, dropped off by the local postman. As the editor works through the book, they might make some changes to existing text, like a PATCH request does; they might rewrite and replace an entire section, like a PUT request does; or they might suggest adding a new section like a POST request. If they were not happy with a part of the book, they might even request to DELETE it.

Working out the right web address (URL)

In our restaurant example, sending our requests to the right person, in this case the waiter or waitress, is essential. We do not want to accidentally ask another customer for our food! When using APIs it is essential to also make sure that we are sending our requests to the right place. However, when using APIs this can be a little more complicated as we must construct a web address that corresponds with what we want to do.

API web addresses are made up of several parts. Take this URL as an example:

https://api.example.org/v1/desserts/56

When you consult the documentation for an API, you might see that a request is documented something like this:

GET /v1/desserts/{id}

You will notice that the first part of the address, https://api.example.org, is omitted. This part of the web address routes to the whole API. Think of it as an address for a company, and everything that follows is different departments.

You may need to be prepared for this first part of the address to change, e.g. a company might have a “test” version of the API that you use for development and then they may have a “production” version with live data on it. In some cases, they may only let you have access to the production API after reviewing your work to ensure it will not cause their systems any problems and data will be kept safe.

The initial “/” character between “GET” and “v1” means

The rest we can break down like this:

| — | — |

|---|---|

| GET | The type of request we are making (see above). In this case we are reading information, not changing it or deleting it. |

| / | If you see a forward slash (/) at the start of an address fragment, it means that the rest of the address is relative to the root of the website. Think of this as giving directions to somewhere in an office block from the reception. Without it, the address would be relative, i.e. in our office block this would be the equivalent of giving directions to someone relative to whichever room they happen to be in at that moment. |

| v1 | The version number of the API. Having versions of the API allows providers to provide new versions of APIs, that may work in different ways, without breaking existing API requests. |

| desserts | This part of the URL tells you the type of resource you will be working with - in this case dessert listings on our menu. |

| {id} | A unique identifier for the resource. This could be a number such as 56 or a string such as “sticky-toffee-pudding”. The curly brackets indicate that this is a parameter provided by the user. |

Assuming your request was successful, the response from the server could be any sort of file type, depending on the resources it handles. If the endpoint deals with metadata, then you might get back a JSON or XML encoded document. These are both ways of representing data in a way that can be easily understood by a computer program.

For instance, a response from our fictional restaurant menu API above might look like this:

{“id”: 56, “title”: “Rhubarb Crumble”, “description”: “A modern take on a classic pudding, served with custard or ice cream”, “gluten_free”: false, “vegetarian”: true, “vegan”: true, “price”: 5.99}

Getting groups of resources

Sometimes, APIs might have functionality that supports returning a group of resources based on a filter. In this case we are providing a field name and the value it must have, in order for that resource to be included in our group.

Let’s take an example where we need a list of vegan desserts that are also gluten free. If you look at the example above you will see that this means we only want resources where the “vegetarian” field is “true” and the “gluten_free” field is also true.

Parameters are added to a request by adding a question mark (?) symbol, followed by the name of the parameter, an equals sign (=) and the value. Additional parameters can be added by adding an ampersand (&) symbol and the name=value pair as before. In our example, we would end up with a URL like this:

https://api.example.org/v1/desserts?vegan=true&gluten_free=true

There will be some practical examples that will step you through how to make different API calls like this in the next section.

How did the request go?

When you make a request to an API you will get a three-digit number returned. This is called the HTTP status code. These codes can be broadly classified as follows:

2XX: The request was understood, the right authorisation was present, and the server could process your request

3XX: The web address you are trying to use is now at a different web address

4XX: You have made an error, this could be caused by the server not understanding your request, or an authorisation problem

5XX: There was an error on the server side. This could be a temporary or permanent problem, it could be caused by things like a fault in the server-side code, or a database being down.

Relevance to the Library Sector (Case Studies/Use Cases)

Why do Libraries and cultural heritage organisations provide and/or use APIs? APIs for Librarians gives a really nice view of the various ways librarians may want to use APIs big and small for various purposes, from displaying Word of the Day on your website to providing access to Internet Archive material. Overcoming disintermediation: a call for librarians to learn to use web service APIs outlines what APIs can enable for our institutions and users. (Free-to-read version available here). Below are some additional use cases for providing and using APIs in a cultural heritage context:

Integrate

The technological beating heart of a modern library is the Library Management System (LMS). This is the electronic brain of a library, but to be able to do its job it must link to many other systems, usually through APIs. This is called Systems Integration.

An example of this is obtaining details about a book that has been bought. The LMS can talk to the publisher’s website through an API to get all the details needed to catalogue the item without the need for someone to manually type it in.

Encourage Reuse

APIs are a great way to help people interact with cultural heritage collections. They allow people to develop new applications that could access your API, maybe in conjunction with many others, to search for types of items across many collections. They enable users, both inside and outside organisations to analyse information, create visualisations and integrate collections data with other systems and workflows.

In the case of digital resources, they can make it easier to reuse and share those resources. For example, the IIIF standard enables images from a cultural heritage institution’s collection to be easily embedded into learning materials produced by a completely different organisation.

Authentication

Most APIs will require authentication in some way in order to use them, ensuring data providers retain some confidence and control over how the data provided is interacted with. This is in place of logging into the website.

The main types of authentication that you will use are:

- API Key – this is a long alphanumeric bit of text that uniquely identifies you to the system.

- OAuth – this is a bit like an API key, but every so often it gets exchanged for a new one. This is more secure as we are not using one card for an extended period of time, but can be more complicated to set up.

Extend

An organisation’s requirements for what it needs from a computer will change over time as technology and society develops. Having an API is a good way to ensure that you will always be able to extend your system to deal with new requirements. Extending functionality in this way is much easier and less risky than modifying a system that has been written as one monolithic unit.

An example here could be if you had to generate a new report from your system. It may already provide some reporting but up until now you have had to take the information from an old report and manipulate it in Excel. This can be error prone and time consuming. Instead, you can use the API to get the information you need and write a program to turn this information into a report. Using an API also has the advantage that you can use an existing system without modifying it or interrupting its uptime. Your code can be entirely separate. (Case Study OpenAthens Reporting API helps librarians demonstrate value)

Extract

Eventually, a computer system will come to the end of its life and need replacing, or maybe a system is being replaced because it did not live up to expectations. In this scenario, being able to get all your data out of that system is critical. An API is an excellent way to do this. It may even be possible to write a program that uses the API of your old system to supply the API of your new system with information, saving everybody a lot of time!

Insurance

Sometimes, circumstances change around a system. It might be that requirements change, or an organisation finds itself doing something new. An API is a kind of insurance policy in these circumstances. It potentially allows you to extend the functionality of a system to meet new challenges. These might be something you need to do continuously, or just once. For example, you might want to bulk update the classification of some books. With an API you could write a program that would go through your collection, look for matching criteria and update accordingly. By always having access to your own data via an API, you have the insurance of being able to react flexibly if circumstances change.

Hands-on activity/self-guided tutorial(s)

Let’s try a few real-world examples of getting information from an API as this is the easiest way to understand the process.

Exercise 1: Using an API for the very first time

1. Introduction

In this exercise, adapted from Using an API: a hands on exercise (a tutorial created for British Library staff by Owen Stephens), you are going to use a Google Spreadsheet to retrieve records from the Flickr API and display the results.

The API you are going to use simply allows you to submit some search terms and get a list of results in a format called RSS. You are going to use a Spreadsheet to submit a search to the API, and display the results.

2. Understanding the API

The API you are going to use is an interface to Flickr, a photo sharing website where many cultural heritage institutions have hosted some of their collection images. Flickr has a very powerful API with lots of functions, but for simplicity in this exercise you are just going to use the Flickr RSS feeds, rather than the full API which is more complex and requires you to register.

Before you can start working with the API, you need to understand how it works. To do this, we are going to look at an example URL:

https://api.flickr.com/services/feeds/photos_public.gne?tags=food&format=rss

The first part of the URL is the address of the API. Everything after the ‘?’ are ‘parameters’ which form the input to the API. There are two parameters listed and they each consist of the parameter name, followed by an ‘=’ sign, then a value.

The URL and parameters breakdown like this:

| URL Part | Explanation |

|---|---|

| https://api.flickr.com/services/feeds/photos_public.gne | The address of the API |

| tags=food | The “tags” parameter is a list of tags (separated by commas) to be used to filter the list of images returned by the API. In this case, just a single tag “food” is used. |

| format=rss | How the results will be presented, in this case using the RSS feed format. |

3. Using the API

To use the API, you are going to use a Google Spreadsheet. Go to https://drive.google.com and login to your Google account. Create a Google Spreadsheet

The first thing to do is build the API call (the query you are going to submit to the API).

First some labels:

In cell A1 enter the text ‘API Address’

In cell A2 enter the text ‘Tags’

In cell A3 enter the text ‘Format’

In cell A4 enter ‘API Call’

In cell A5 enter ‘Results’

Now, based on the information we were able to obtain by understanding the API we can fill values into column B as follows:

In cell B1 enter the address of the API

In cell B2 enter a simple, one-word tag

In cell B3 enter the text ‘rss’ (omitting the inverted commas)

The first three rows of the spreadsheet should look something like this (with whatever tag you’ve chosen to search for in B2):

You now have all the parameters we need to build the API call. To do this you want to create a URL very similar to the one you looked at above. You can do this using a handy spreadsheet function/formula called ‘Concatenate’ which allows you to combine the contents of a number of spreadsheet cells with other text.

In Cell B4 type the following formula:

=CONCATENATE(B1,“?”,“tags=”,B2,“&format=”,B3)

This joins the contents of cells B1, B2 with the text included in inverted commas in formula. Once you have entered this formula and pressed enter, your spreadsheet should look like:

The final step is to send this query, and retrieve and display the results. This is where the fact that the API returns results as an RSS feed comes in extremely useful. Google Spreadsheets has a special function for retrieving and displaying RSS feeds.

To use this, in Cell B5 type the following formula:

=importFeed(B4)

Google Spreadsheets knows what an RSS feed is, and understands that it will contain one or more ‘items’ with a ‘title’ and a ‘link’. It will do the rest for us. Hit enter, and see the results.

Excel sheet with the relevant API information.

Congratulations! You have built an API query, and displayed the results.

You have:

* Explored an API for Flickr

* Seen how you can ‘call’ the API by adding some parameters to a URL

* Understood how the API returns results in RSS format

* Used this knowledge to build a Google Spreadsheet which searches for a tag on Flickr and displays the results

4. Going Further

Further parameters that this API accepts are:

- id

- ids

- tagmode

- format

- lang

These are documented at https://www.flickr.com/services/feeds/docs/photos_public/. When adding parameters to a URL, you use the ampersand (‘&’ sign) between each parameter. For example:

https://api.flickr.com/services/feeds/photos_public.gne?tags=food&id=23577728@N07

This searches for all photos tagged with ‘food’ from a specific user with id = 23577728@N07

By adding a row to the spreadsheet for this parameter, and modifying the ‘concatenate’ statement that builds the API Call, can you make the spreadsheet only return images with a specific tag in the British Library Flickr collection? The Flickr ID for the British Library is 12403504@N02

Exercise 2: Find out information for a location using Google APIs

1. Go to https://developers.google.com/maps/documentation/places/web-service/text-search in your browser

2. Click on “Web Service” as the platform

3. You may be asked to log in using your Google account.

4. Click on the “API” button in the right-hand section.

5. Click on the “Fullscreen” icon along the top of this section, it is the icon that looks like edges of a square.

6. In the APIs Explorer window, click on “HTTP” – this lets you see the API request in terms of the web requests that are made.

7. The “Request Body” has a single parameter called “textQuery” which you can use to search for a place you would like to know more about.

8. Try a place you know, for example “British Library” as the value.

9. Click “Execute”.

10. You may be prompted to login and authorise the API request to continue.

All being well you will see a response in the right-hand side. “200” will be prominently displayed, you might remember this code from the “How did the request go?” section earlier. Underneath, you will see a structured response with everything Google knows about that place. Notice that a lot of information is mixed in together, for example what type of location it is, coordinates on a map and opening hours.

Other online tutorials for beginners to try:

- Joshua Dull has created a useful workshop in the style of the Library Carpentries, called APIs for Libraries

- OpenLibrary has some APIs you can experiment with directly in your browser: https://openlibrary.org/developers/api and I can particularly recommend having a play around in their sandbox which gives a great illustration of the code involved in API requests and API responses: swagger/docs | Open Library

- The Programming Historian has a lot of great API tutorials you can try which will walk you through using APIs for different purposes such as Fetching and Parsing Data from the Web with OpenRefine

Once you’re feeling a little more confident, these tutorials will help you go further:

- Wikimedia offers some incredibly useful APIs of particular interest to libraries who contribute to or have collection items there. They have an entire tutorial to help beginners: Getting started with Wikimedia APIs - API Portal

- Dataquest has a nice tutorial on using the Python language to call APIs: How to Use an API in Python

- You can even use APIs to integrate with the latest AI tools. Here are some examples from OpenAI: Developer quickstart: Take your first steps with the OpenAI API.

- Once you are a bit more confident with how APIs work, why not try designing one? For example, how would you go about designing an API for a publisher to allow them to keep track of books, editions and authors? This guide should help: RESTful web API design.

Recommended Reading/Viewing

Many great resources are available on the web to tell you more about APIs:

- Introduction to APIs | DARIAH-Campus

- What is an API? from IBM https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/api

- What is a REST API? from Postman: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PfujVETI-i4

- What is a REST API? from IBM: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lsMQRaeKNDk

- UK Government list of APIs: https://www.api.gov.uk/#uk-public-sector-apis

- Trove API introduction - GLAM Workbench

Some highly relevant APIs for libraries and/or researchers: - OpenAlex is a free API that provides similar information to Scopus and Web of Science. - CrossRef provides a free API to search and access metadata for all of their DOIs.

Finding Communities of Practice

This guide is intended only as a first step for starting your journey with APIs and as you start experimenting and getting hands-on experience you will undoubtedly have further questions or need for support from those who have more experience with APIs. Here are some suggestions:

- Many organisations providing APIs will have support or contact info for questions and troubleshooting so look out for those.

- You can also join a community such as the AI4LAM community where you can connect with lots of professionals working at the intersection of technology and cultural heritage.

- Stack Overflow is a popular discussion board where you can post your software related questions.

- Look for local in-person or online Hackathons which are often focused on using a specific API.