IIIF

A one page guide introducing the basics of the IIIF standard with case studies and practical advice for getting started.

TBD, TBD

Introduction

IIIF (pronounced “triple-eye-eff”) stands for the International Image Interoperability Framework. Quite a tongue twister that one, but it broadly represents two things:

- a set of open standards for delivering high-quality, attributed digital objects online at scale.

- the open, international community of software developers, libraries, researchers, educators, museums, universities, creative agencies, and more working together to develop and implement the IIIF APIs to make the above open standards happen.

Open Standard

Ever try to look at a large high-resolution digitised manuscript online only for it to take ages to load, and when it finally does you have no way to actually move around the image easily nor see any of the metadata or annotations related to it?

Or maybe spent months on end negotiating the terms and methods around sending copies of a variety of differently sized individual images to another institution for them to host as part of collaborative project?

IIIF brings a whole new efficiency to the way in which we in the cultural heritage sector go about sharing and making our digitised collections available online, while greatly expanding the functionality around the way users interact with them. It’s an open standard, collaboratively developed and maintained by a host of cultural heritage institutions around the world that defines a consistent method for the delivery of images and audio/visual files from servers to different environments on the Web where they can then be viewed and interacted with in many ways.

IIIF basically specifies a way for browsers to display an image or audio/visual files in a way that enables much richer functionality on the Web:

- Makes it easier to display large images on the web in a way that is scalable (enabling deep zoom)

- Allows easy comparison between two objects, connecting and uniting materials across institutional boundaries

- Displays structure and metadata and annotations with the digital collection item. (For a digitised manuscript for instance this might be page order and searchable text, for audio/visual materials, that means being able to deliver complex structures (such as several reels of film that make up a single movie) along with things like captions, transcriptions/translations, annotations, and more.)

“At its simplest, IIIF uses APIs to load images quickly and zoom smoothly without additional loading time. But IIIF also allows you to do much more, including pulling IIIF-enabled images from different sites into viewers for comparison without downloading them (at full resolution), and enabling saving links to details of images or portions of A/V files for future reference. IIIF also allows you to use many open-source tools that help you to compare, annotate, transcribe, collaborate, and more. You can even gather multiple IIIF images together from across multiple archival collections and/or institutions to create projects or exhibits without advanced technical skills”. -From IIIF for Archives

Making your collections IIIF enabled makes it easier to share your content online in a consistent way, enabling portability across different IIIF enabled viewers. This means that rather than endlessly creating copies and different access versions of your images to send all over the world for different projects, they can stay on your same IIIF Image server, but be accessed and displayed by viewers hosted at institutions elsewhere in any fashion you require.

Open Community

The IIIF community is made up of over 100 major cultural heritage organisations worldwide who have formally adopted it, including many of our very own LIBER members. It was started in 2011 as a collaboration between The British Library, Stanford University, the Bodleian Libraries (Oxford University), the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Nasjonalbiblioteket (National Library of Norway), Los Alamos National Laboratory Research Library, and Cornell University. It’s a really nice example of an open, grassroots but global community effort, backed by a consortium of leading cultural institutions, who have been working together to develop and implement this new capability for decades and solve their shared problems with delivering, managing, sharing, and working with their resources.

What would I need to do to make my collection IIIF enabled?!

If you want the deep nitty gritty technical stuff around all the APIs and how they fit together there is quite a bit of implementation documentation on their website that goes into all this. But essentially, the basic set up behind making your own digitised collections “IIIF enabled”, as they say, looks a little something like this:

- Set-up a IIIF image server (you can choose one developed by the community, or there are IIIF-compatible image servers available from vendors or other web hosts), move your content there and implement the IIIF Image API to make those images and audio/video materials available from there.

- Implement the IIIF Presentation API which creates the all important IIIF Manifest files (also many open source or vendor products can help handle this bit too) for each of your objects. This Manifest file is really the prime unit in IIIF, it essentially combines and packages in json code, information about your images and structural data from your metadata source. It lists all the information that makes up your new IIIF enabled object, from how to display it to what information IIIF viewers should (and should not) display (such as structure or the order of pages, or even as minute as where an illustration is located within an image if you like). If you want to see an example of what one looks like this is a IIIF Manifest from the Bodleian Libraries at University of Oxford relating to this collection item. Each manifest has its own URL and that’s the bit you’ll use to do cool things with the object in different IIIF viewers, such as allowing a manuscript to be easily dragged and dropped into Mirador for instance for comparison with other IIIF enabled manuscripts.

- Choose one of the many IIIF enabled viewers for displaying your images and add it to your own collection site. Again, looking at that same collection item record above, note in the upper left hand-corner (see image below) there is an option to view in Mirador or Universal Viewer which are two different styles of IIIF viewer that afford different functionalities.

- Consider making your IIIF Manifests available publicly for download so users can work with them in all the interesting ways you’ve now enabled!

Relevance to the Library Sector (Case Studies/Use Cases)

IIIF was initiated by a bunch of libraries and cultural heritage collections holders and it shows! It was proposed in late 2011 as a collaboration between The British Library, Stanford University, the Bodleian Libraries (Oxford University), the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Nasjonalbiblioteket (National Library of Norway), Los Alamos National Laboratory Research Library, and Cornell University. The intention of the consortium has always been to combine resource and effort in building viewers that reflected the way we wanted our digital collections to be displayed online, rather than everyone still spending time and resource making our own custom viewers and building our own content silos. It’s brought a huge amount of efficiency too in the way that we share images with each other and researchers. It’s changed the way collaborative projects are undertaken where endless metadata mapping exercises, contract negotiations around re-use and hosting, and the copying and shipping of digitised materials on external hard drives were the norm.

There are quite a number of use cases and case studies available on the IIIF Demos page but let’s have a quick look at three real life (and canonical) examples of IIIF in action.

Deep Zoom and Annotations

The example here is of the Ōmi Kuni-ezu 近江國絵圖 Japanese Tax map created in 1837. It’s meant to be read in the round by someone standing in the middle–you can see the scale when this zooms out– the map is eleven by seventeen FEET, and the person standing next to it, Wayne who works in the library at Stanford, is six feet four inches tall. This image is a composite of 158 individual images with a file size of 1.27Gb. IIIF allows just enough of an image to be delivered to a viewer–going from a whole image to just the part that they are zooming in on. Without IIIF, an end user might have to download an extremely large file, but using IIIF provides a smooth and easy viewing experience.

Have a play and view this image in their Universal viewer here

Virtual Reconstruction

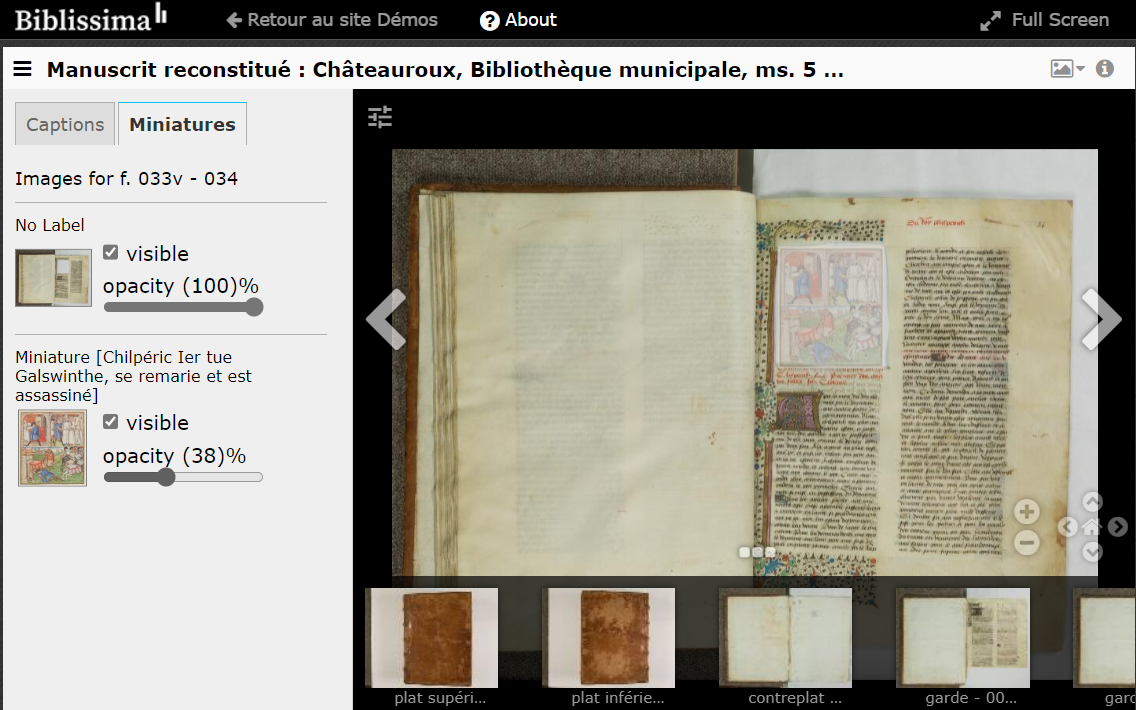

The virtual reconstruction of this damaged manuscript from Châteauroux in France (Grandes Chroniques de France, ca. 1460) is probably one of the most well-known and best examples of the power of IIIF to support this use case (and my own personal favourite!). At some point in the manuscripts history, fourteen of its illuminations were cut out. These illuminations eventually ended up at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in the 19th century and were digitised individually. In the demo you see the reuniting of the miniatures with the full manuscript as IIIF allows a virtual repositioning of the cut out decorations with the text, virtually reconstructing the manuscript online using the Mirador Viewer so it reflects its original state.

I highly recommend having a play around with the Mirador Viewer: Châteauroux demo.

Hands-on activity and other self-guided tutorial(s)

The following tutorials are two of my favourite recommendations for colleagues interested in having a play with IIIF manifests yourself and in the process gaining a practical understanding of how they work, and the benefits!

- IIIF Online Workshops The community itself has created a number of excellent and free self-paced tutorials and though they host live online workshops for a fee, these are recorded and available and useful for newcomers for free afterwards. In fact staff at British Library have walked through these self-guided resources online quite often with great success. There is also the opportunity to hire a IIIF Trainer to come to deliver live bespoke training directly to your institution (for a fee), which we have also partaken in!

- Working with IIIF images in education, communication and research This is a self-guided workshop available online in Dutch and English and has some excellent exercises to get you familiar with finding IIIF manifests in catalogues and importing them into different viewers. I highly recommend making some time (they recommend 120 minutes) to read through this and try out some of the exercises.

Recommended Reading/Viewing

There is a useful collection of articles and data related to IIIF being compiled by the community on Zenodo

The IIIF organisation has also created a number of useful resources alongside their training materials such as How It Works, a plain-language guide to how the IIIF API’s work and a glossary of “Key concepts you’ll encounter when working with IIIF”.

It’s worth having a look at how other institutions have provided IIIF Resources.

There is also a massive list of learning resources, Awesome IIIF, compiled and maintained by the IIIF Community if you are looking to take your knowledge a bit further and dig deeper into some of the exciting implementations of IIIF.

Finding Communities of Practice

Learning about IIIF can be overwhelming at first, especially if you’re not a programmer, but the IIIF Community is a very supportive and engaged one and has created a number of ways to get involved and find support and help.

I recommend checking out their community page IIIF Community to find details of their next open community calls, or to join their Slack Channel where you can post questions and join the discussion with other users.